BA

Political Science

Howard University

2003

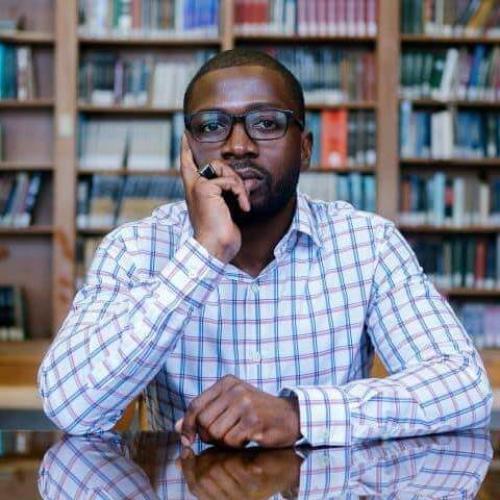

Brandon is an associate professor of philosophy. He earned a BA from Howard University, JD from Harvard Law School, MA in philosophy from Tufts University, and PhD in philosophy from the University of Pittsburgh. His doctoral dissertation, on Hegel's theory of punishment, was supervised by Robert Brandom.

He writes and thinks about various topics in political philosophy, philosophy of law, and African-American philosophy. He is co-editor of The Movement for Black Lives: Philosophical Perspectives (Oxford University Press, 2021). His article, "Hegelian Restorative Justice," is forthcoming in the Southern Journal of Philosophy. He is currently thinking about philosophical arguments for slavery reparations.

When he is not philosophizing, he serves as a volunteer high school wrestling coach.

Political Science

Howard University

2003

Harvard Law School

2008

Philosophy

Tufts University

2008

Philosophy

University of Pittsburgh

2013

As we know, the United States never paid large-scale reparations to formerly enslaved Black people or their descendants. Some believe that justice requires the U.S. to compensate the descendants of those victimized by American slavery. Others take it that it would be unjust and unfair to require the current American government to pay for the sins of the past. In this course, we’ll consider all sides of the philosophical debate over Black reparations.

The scholarship of Derrick Bell, acclaimed critical race theorist and constitutional law scholar, continues to animate discussions outside and inside of legal academia. Cornel West, for example, recently criticized Ta-Nehisi Coates’ pessimism about racial progress, arguing that Coates’ approach lacks the appeal to black struggle that is present in Bell’s work. Furthermore, many critical race theorists take Bell’s interest convergence principle and racial realism thesis as starting points for their scholarship. Law professor Paul Butler, for example, draws on both of Bell’s theories to explain the persistence of racism in American policing. Legal scholar Justin Driver, on the other hand, views Bell’s theories as problematically pessimistic about the prospect of true racial justice in the United States. I argue that Bell’s approach to racial justice is viable and instructive, but that it must be modified if it is to overcome several serious theoretical problems. The interest convergence principle entails that groups are largely amoral, while the racial realism thesis includes the claim that black Americans should act on moral reasons. Thus, the principle and the thesis, taken together, entail a contradiction.

In the Philosophy of Right, Hegel claims that crime is a negation of right and punishment is the “negation of the negation.” Punishment, for Hegel, “annuls” the criminal act. Many take it that Hegel endorses a form of retributivism—the theory that criminal offenders should be subject to harsh treatment in response and in proportion to their wrongdoing. Here I argue that restorative criminal justice is consistent with Hegel’s remarks on punishment and his overall philosophical system. This is true, in part, because restorative justice integrates Hegel’s instructive discussion of confession and forgiveness in the Phenomenology of Spirit. Hegel claims that true moral relationships allow space for persons to confess their moral shortcomings and forgive the shortcomings of others. Restorative criminal justice brings the perpetrators and victims of crime together to offer confessions and forgiveness and to work to heal the various wounds caused by crime. I do not claim that Hegel must be read as advocating restorative justice. While Hegel tells us what punishment does, he does not commit himself to any form of punishment. What I offer here is a rational, progressive reconstruction and extension of Hegel’s conception of crime and punishment.